Decline In Volunteer Firefighters Slows Response Capabilities

By Meiying Wu, Rachel Thomas, Lexi Churchill and Camden Jones

Mid-Missouri Small-Town Fire Stations Struggle with Funding, Volunteer Numbers

Missouri’s volunteer departments are understaffed, underfunded and struggling to keep their communities safe.

About 75 percent of the state’s fire departments are volunteer-only, according to the National Fire Protection Association, an industry group. And if you talk to some of the firefighters who give up their time to save their neighbors’ homes or farms, you hear one thing over and over:

There are fewer of us than there used to be. And it’s getting to be a problem — a national problem.

Since 1986, the number of volunteer firefighters in the U.S. has been decreasing, according to a 2016 NFPA survey.

David Decker is president of the Lincoln Community Fire Protection District Board of Directors in Benton County. Local taxes only generate about $100,000 a year for his department.

“Everything is so expensive,” Decker said. “You've really got to make do with the things you have. … Keeping things going on a limited budget — that's a delicate balancing act at times.”

Kevin Zumwalt, associate director of the University of Missouri Fire and Rescue Training Institute, says $100,000 isn’t the lowest budget he’s seen for a small department. The nearby town of Clarence, for example, has an annual budget of just over $13,000.

“That's not a lot of money,” Zumwalt said. “That's barely putting fuel in the fire truck. That's barely keeping the lights on in the fire station. ... That's barely having a concrete floor … for your trucks to park on.”

Volunteer departments have to come up with creative ways to pay for equipment and training. These can include fundraising activities and data reports to the Missouri Department of Conservation and the National Fire Incident System in order to be eligible for state and federal grants.

MU’s fire training institute helps provide training to Missouri fire departments. The institute recently received funding from the MFA Incorporated Charitable Foundation and equipment donations from Brock Grain Systems to support a grain engulfment rescue training program in Lincoln on Feb. 18.

But this kind of free access to training for volunteers does not necessarily enable all of them to attend.

Though the Missouri Division of Fire Safety provides registration and certification to fire departments throughout Missouri, there is no state or federal law that requires any training for volunteer firefighters.

Mike Holcer is Meadville’s fire chief and director of Missouri Association of Fire Chiefs Region B. He says it’s rare for small departments to have a majority of firefighters who have completed Firefighter I and II, Missouri’s basic firefighter training and certification programs. Holcer estimates the programs took about 10 months to complete when they were taught at the Meadville department, totalling around 240 hours.

Holcer works for the U.S. Department of Agricultural Natural Resource Conservation Service when he isn’t volunteering.

“If we have a call during the day and I'm around the office or in the area, I'm able to take off and go to the fire,” Holcer said. “Some of our guys are not. We all go to work just like anybody else.”

Without the worry of balancing other jobs with firefighting, career fire departments are able to respond from the station 24 hours a day.

Volunteer firefighters, on the other hand, have to be alert at all times.

“Whenever the pager goes off, you don’t go, ‘Oh no, here we go again,’” Scott said. “You just instantly put your clothes on, and you’re gone. … There’s no stopping. … It sounds crazy, but you get it in your blood, and you’ve just got to do it.”

Even ready and willing volunteers can only do so much to work around their schedules. Holcer says responding volunteer firefighters’ have to first get to the station from wherever they are and then take the trucks to the fire site.

“At night when people are home, our response times are better,” Holcer said. “During the daytime, ... we normally don't have a lot of guys around, so our response times are somewhat longer.”

The lack of a regular schedule creates an “always on” attitude in the volunteers.

“Once we’re off our shift, we all have our homes that we got back to,” said Jeffrey Heidenreich, a full-time firefighter for the Columbia Fire Department. “I would bet that the typical, average volunteer firefighter puts in 20 or more hours a month with their volunteer fire station. That's a lot to ask someone when they have careers and school and families. ... It's probably easy to get burnt out.”

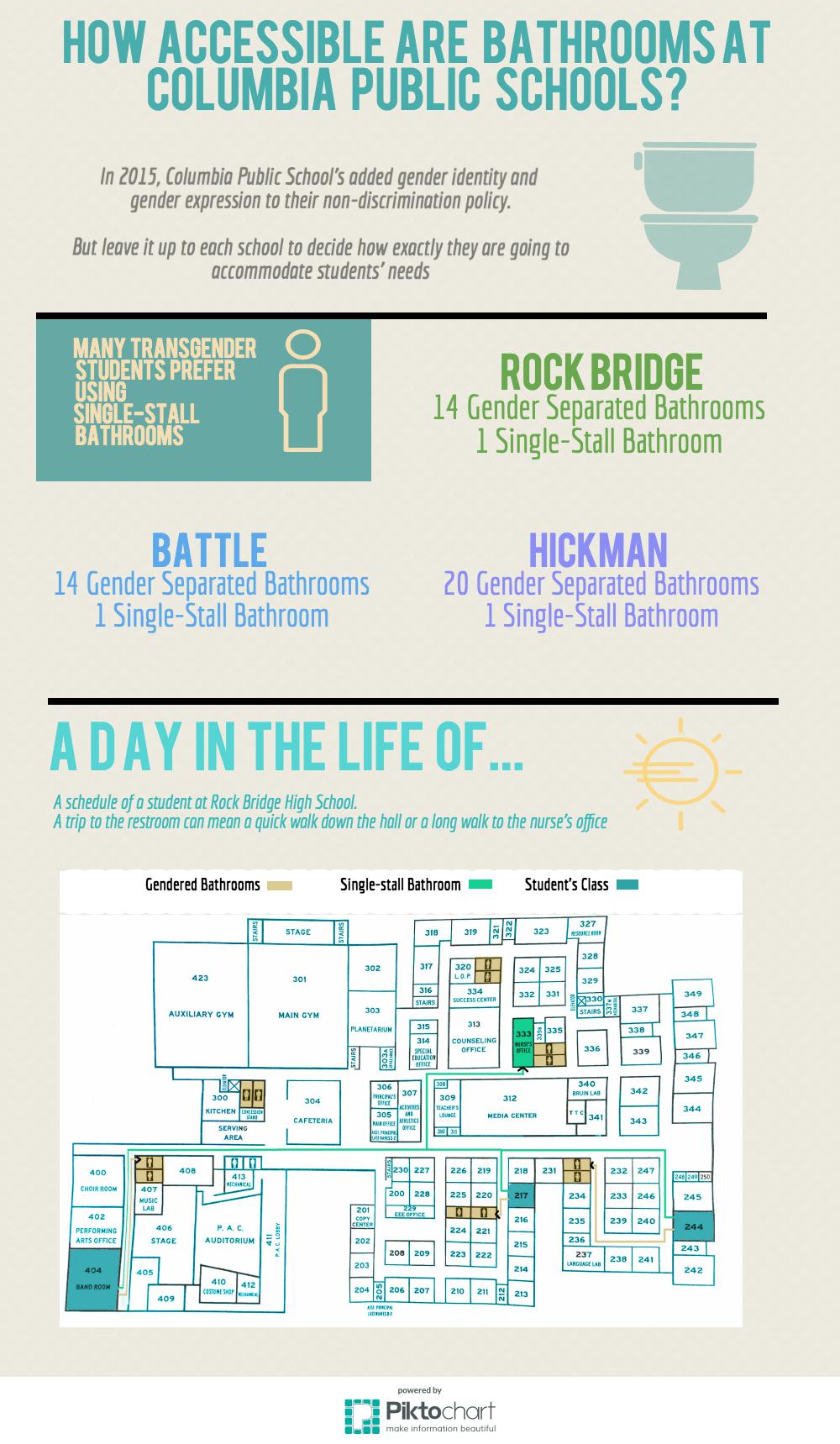

Guidelines leave transgender students’ rights in question

By Meiying Wu, Lexi Churchill, Humera Lodhi and DJ Pointer

Transgender Bathroom Rights Questioned Nationally

A pixie cut, “The Narrows” t-shirt and thin black choker dotted with a single pearl - that’s what made up Ian Koopman’s image Tuesday, March 7.

As a transgender man at Rock Bridge high school, the senior knows it might not be a typical masculine look. But it's what he liked for that day. This is how he exists.

For Ian, conversations about the rights of transgender people happening at the state and national level are missing the point. The country is focused on bathrooms, but for Ian, it’s about so much more.

“If you just try to make it about restrooms you're really sort of dodging the essential question of how we view trans people in society and what we think their rights are as human beings,” Koopman said. “It's just how we view people in our society and if we really think people should be second class citizens.”

Koopman continues to use the women’s restroom, the space he’s always been comfortable in. But not all transgender students share this preference.

Over the past several years, the national discussion about transgender rights focuses on bathrooms. Questions like what facilities transgender students can use and how to implement those rules have challenged legislators nationwide.

Under the Obama Administration, transgender students’ rights were expanded under Title IX, the government’s civil rights statute. This addition allows transgender students to use the bathroom of the gender they identify with.

Within the first few weeks of its term, the Trump Administration reversed this protection.

In response to new reversal, the United States Supreme Court sent a transgender bathroom case back to lower courts to be reconsidered. Because Trump’s policy change came after the court’s ruling, by the time the case made it to the Supreme Court, it was not up to date.

Sandra Davidson, an MU law professor, said when there is insufficient information in a case, the Supreme Court sends it back to fill in the holes.

Davidson also said the stall may come down to a lack of justices.

“Right now we do not have a complete Supreme Court,” Davidson said. “Especially on these issue that are divisive, and I should imagine this one might be, if you think you’re going to have a 4-4 split so that the lower court decision is going to be the one that will stand up anyway, you might want to wait and see if you’re going to have another colleague.”

At a lower level, states are taking the issue into their own hands. There’s been a number of conflicts in states like Maine and North Carolina that passed laws reconstructing transgender rights.

In Missouri, a similar policy is also looking to redefine transgender rights. Missouri Senator Ed Emery, R-Lamar, has proposed a bill that requires students to use the restroom of their “biological sex” when in “states of undress” in public schools.

This is the second year Emery has proposed this bill. Last time it didn’t receive a hearing, but this year it’s been taken up by a Senate committee.

To Emery, this bill maintains long standing expectations in public school privacy.

“It would really be no different than it always has,” Emery said. “The difference is that now we have these new kind of imaginary genders that don't occur biologically or scientifically. They just occur in the mind and so now that the courts and the Obama Administration have essentially created these new genders and until just very recently we've had two genders.”

Emery said the purpose of the bill is to protect the privacy of all students, not just transgender ones.

However, transgender people that are affected by these policies, like Koopman, are concerned about the practicality of policy implementation.

“Is there even a way you can enforce this in an ethical manner when you're dealing with minors at school?” Koopman asked. “The only way you check assigned genders is by looking at genitals. So I just don't even know how any sort of school official would tackle that, or even feel comfortable doing that to students.”

For Koopman, the bill represents a lack of support for the transgender community.

Koopman also points out that not all students’ appearance stands out. Many pass as cisgender on a daily basis.

Therein lies an administrative problem. Knowing who is being regulated is no simple task.

Insurance market changes leave some mid-Missourians out in the cold

By Meiying Wu, DJ Pointer and Rachel Thomas

Mid-Missouri farmers’ health care improves with the Affordable Care Act

In early February outside the Boone County Courthouse, fifth-generation livestock farmer Rhonda Perry stood in unison with farmers and activists at the Columbia Health Care Bus Rally event, chanting “When ACA is under attack, what do we do? Stand up fight back!”

Perry and the rest of the crowd had arrived on a charter bus that read “Save My Care” in bold letters. They made their message clear; that farmers want affordable health care. The event was coordinated by the Missouri Rural Crisis Center, a non-profit organization that caters to the needs of family farmers.

Those needs are apparent when farmers like Perry have pre-existing conditions, and could never pay the bills required for hospitalization and medication.

“For several years I did not have any insurance at all, and then I was able to get insurance through MRCC and thank God I had, because I was diagnosed with a really rare cancer,” Perry said.

She was hired at the crisis center as the program director. She remembers how lucky she was to find an off-farm job that provides quality health insurance. But she said other farmers who rely on the private marketplace for health care aren’t so fortunate.

According to a health insurance survey done in 2007 by the crisis center and the U.S. Department of Agriculture, 91 percent of Missouri farmers reported having individual insurance plans provided by private insurance companies instead of on the market. This resulted in farmers on average spending $2,117 more on health care than those insured through off-farm employment. The survey concluded that farmers’ insurance expenses affected their ability to pay rent 40 percent of the time and other bills 80 percent of the time. Most importantly, it caused them to delay farm or ranch investments 40 percent and increased the need to take off-farm jobs to help pay medical bills.

Perry is concerned for her neighborhood farm community who cannot afford private insurance plans.

“One of the things that I wonder is does everyone get the same treatment if you don’t have insurance? The amount of stress that, that creates in rural communities is pretty incredible,” Perry said.

When the Affordable Care Act was implemented in 2010, the situation for these farmers changed significantly. Now, farmers who have pre-existing conditions can no longer be charged for it. Some farmers under the health care law even qualify for a tax credit from the government that can help pay toward their monthly premium.

Health law professor Sidney Watson of Saint Louis University works on behalf of low-income people and she teaches her classes about the regulations of the health care law.

“What the Affordable Care Act did was make it illegal to charge farmers more for their hard work, so they can’t be charged more,” Watson said.

She said if there were to be a current survey about family farmers and their health insurance, the premiums and deductibles would be much lower now with the health care law into play.

Audrain County farmer Paul Harter agrees. He said that before the health care law, he could only afford to put his wife and his daughter under their insurance, leaving him to go without coverage.

“When the ACA came in, we went ahead and got health care coverage because now it was affordable adding me on. So it's been a good thing as far as that's concerned in the beginning,” Harter said.

Since its enactment, the health care law has made it accessible for farmers to get affordable health insurance. But, some farmers are facing another hurdle. They fall into what is called the coverage gap.

The Kaiser Family Foundation defines the coverage gap as a space where adults have incomes above Medicaid eligibility limits but fall short to make enough to qualify for Marketplace premium tax credits.

According to Healthinsurance.org, Missouri is a state that has not accepted federal Medicaid expansion and in 2016, there were about 109,000 people who had no realistic access to health insurance without the expansion.

Crisis center communications director Tim Gibbons partners with other non-profit organizations to allow its members to testify at House and Senate Medicaid Expansion interim committee hearings about why Medicaid expansion is a priority for mid-Missouri farmers.

“Medicaid expansion is vital for rural people. Farmers and rural people have less access to employer sponsored health care, they have less providers, insurance is more expensive, and there is less competition within the insurance marketplace for rural people,” Gibbons said.

Gibbons said lack of competition in the marketplace has been bad for consumers and producers alike.

Who holds MSHSAA’s concussion reports accountable?

By: Meiying Wu, Rachel Thomas, Sierra Morris and Jiayi Wang

Social Media Teaser

For parents and coaches of school athletes, safety is a high priority. In 2011 Missouri passed a bill to track concussions in youth sports. The goal was to protect student athletes. KBIA’s Rachel Thomas explains why enforcing this law is so difficult and what it means for student athletes.

Missouri Pushes for More Concussion Prevention

In fall of 2015, Bennett Lawson, a sophomore at Rock Bridge High School, made head-to-head contact with a teammate during a warm-up before a football game. Lawson’s coach and trainer recognized concussion symptoms and immediately pulled him off the field. Lawson was not allowed to return to play until he received clearance from a health professional a month later.

Lawson was just one of more than 3,000 reported incidents of youth athlete head injuries in Missouri in 2015. Because of Missouri’s youth sports brain injury laws, he was prevented from returning to play until he had recovered.

Since 2014, all 50 states have created legislation to address youth athlete brain injuries. Most states have laws similar to Missouri’s. They require concussion education, immediate removal of athletes on suspicion of concussion and returning them to play only with approval from a doctor.

However, Missouri is attempting to take concussion prevention a step further. It is the only state whose law requires an annual report on youth sports brain injury.

Starting in 2011, the Missouri State High School Activities Association compiled youth athlete concussion data from its public school members. According to Missouri law, MSHSAA is required to publish an annual report, known as the Interscholastic Youth Sports Brain Injury Prevention Report, and distribute it to its member schools.

However, there are loopholes in the law that allow inconsistent data and a decline in schools participating in the report.

There was a 10 percent decrease in schools that reported from 2015 to 2016 and no penalty for schools that did not report.

Greg Stahl, MSHSAA’s assistant executive director, said this decrease could be due to several factors. He said the submission date for the 2015-2016 report occurred in the summertime when some schools are closed. School administrators, who only have nine or 10 month contracts, are unable to work during that time. MSHSAA hopes to increase school participation by moving the submission date earlier before schools close for the summer.

The law requires MSHSAA’s report to be submitted to education committees within the state House of Representatives and state Senate. However, the committees do not take time to review the report.

Bryan Spencer, vice-chairman of the House Committee on Elementary and Secondary Education, said there isn’t enough time or resources for any committee to oversee the data within the report.

“Nobody looks at it, until there is a problem,” Spencer said.

The lack of oversight enables MSHSAA to pick and choose what data to include in their reports. In 2014, the number of member schools included in the report dramatically decreased. MSHSAA decided to exclude middle school data from the report.

Despite the inconsistent number of schools included in the reports, the rate of youth sport head injury in Missouri has increased by 40 percent since 2012.

Harvey Richards, previous MSHSAA associate executive director, said this increase is not due to more concussions, but is because the increased concussion education and training have equipped more coaches, trainers and parents to recognize and report signs of concussions.

In order to address this, Richards said MSHSAA will be adding more specific questions to next year’s report.

“Were you removed from play? Yes. When you came back was it diagnosed as a concussion? So we’re going to get two sets of numbers there. So the numbers will even look different next year,” Richards said.

MSHSAA’s past reports only include occurrences when youth athletes were removed from play because of symptoms of concussion. Not all occurrences in the report were diagnosed concussions.

Despite the difficulties that accompany enforcing an annual report, tracking youth sports brain injuries is beneficial. If Lawson were to have another concussion in the future, Rock Bridge High School would be able to track his head injury history. The school can use this data to keep track of its individual students, as well as overall trends for each sport.

Pat Lacy, Southern Boone County R-I School District’s athletic director, said before Missouri created its youth athlete brain injury laws, coaches and student athletes didn’t take head injuries as seriously.

“[Athletes] went back into athletic events, maybe even on the same day, if they had a head injury in a football game. It just wasn’t looked at like it is now,” Lacy said. “Now we have trainers on the sidelines. They’re going to make the decision, they’re going to say, ‘no they’re not going back into the contest.’”

By tracking their students’ head injury trends and history, Southern Boone school district coaches noticed head injuries occurring consistently in soccer. In response, Lacy said they’ll be purchasing concussion headbands for all of their high school soccer players. The headbands will lighten the impact of any hit to the head.

The youth sports brain injury data collection is unique to Missouri not only by state comparison, but nationally as well. There is currently no established national surveillance system to gather and track national youth sport brain injuries. It is currently impossible to compare Missouri’s youth athlete concussion data to accurate nationwide estimates because they don’t exist.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention want to change that. Since 2016, the CDC has been advocating for a National Concussion Surveillance System that will monitor national trends and see the effects of prevention efforts. The system is estimated to cost $5 million.

According to the CDC, only one out of every nine concussions nationwide may be reported with the current data sources. If implemented, the National Concussion Surveillance System would compile its data by a nationwide household telephone survey. The survey would include how many children and adults had concussions and the cause of injury.

With nationwide data on concussions, the CDC said it will be able to provide national estimates specifically on youth sports concussions and people living with a disability caused by brain injury.

Midwives are becoming a popular choice, but lack regulation

By: Meiying Wu, Jiayi Wang, Rachel Thomas, Humera Lodhi

Missouri midwifery law may put mothers at risk

In 2009, lay midwife Elaine Diamond oversaw the home birth of a Springfield mother. Diamond allowed the mother to labor for over 48 hours and refused her requests to go to the hospital.

The mother was eventually taken to Mercy Hospital Springfield, and the baby was delivered in the parking lot. The baby suffered severe brain damage and died less than a week later.

The doctors at Mercy Hospital Springfield said that, in the right setting, the baby could have been safely delivered, according to a story published in the Springfield News-Leader.

Seven years later, Diamond pleaded guilty to endangering the welfare of a child and unauthorized practice of medicine, according to a news release from the office of the Greene County Prosecuting Attorney.

Dee Wampler, Diamond’s attorney, said the problem was that Diamond did not complete any medical or midwifery training.

“My lady didn't want to take any training,” Wampler said. “She just believes that God told her that this was what she was supposed to do.”

Until midwifery was legalized in Missouri in 2007, it was a felony for lay midwives to practice midwifery in the state. A lay midwife is a midwife who does not have a license to practice medicine.

In 2005, former state Rep. Cynthia Davis, R-O’Fallon, proposed a bill specifying that nothing may prohibit a woman from giving birth with the caregiver of her choice. Potential caregivers included lay midwives who provided services other than the practice of medicine, nursing and nurse-midwifery.

“The women who did want it were people who believe that women are smart enough to know what’s in their best interest,” Davis said of her proposed bill. “We don’t have to have laws to protect the little ladies from making terrible mistakes.”

The bill was passed by the Missouri House of Representatives but failed in the Missouri Senate. But it set the stage for legalization of midwifery the next year.

In 2007, midwifery was legalized in Missouri after former Sen. John Loudon, R-St. Louis, surreptitiously slipped a sentence into a 123-page health insurance bill. The sentence stated that “any person who holds current ministerial or tocological certification by an organization accredited by the National Organization for Competency Assurance may provide services.”

“Tocological” is an ancient Greek word and a synonym for “obstetrics,” the branch of medicine concerned with childbirth. The sentence allowed lay midwives to legally deliver babies in Missouri.

No one realized what Loudon had done. That is, until former state Rep. Sam Page, D-Creve Coeur, noticed the added sentence and told his colleagues about it. But it was too late to debate -- the Senate had already made its final vote.

The bill's lead sponsor, former state Rep. Doug Ervin, R-Holt, said that Loudon had deceived him, according to an article published by the Southeast Missourian.

Loudon was removed as chairman of the Missouri Senate Small Business, Insurance and Industrial Relations Committee by President Pro Tem Michael Gibbons.

The Missouri State Medical Association and three other organizations filed suit to invalidate the section that would allow legal midwifery practice. The Missouri Supreme Court, however, ruled in a 5-2 decision to uphold the law. The ruling indicated that MSMA had no standing to challenge the constitutionality of the law.

A year later, things became more controversial when the National Organization for Competency Assurance changed its name to the Institute for Credentialing Excellence.

“That organization is now gone. It's been renamed,”said Tom Holloway, executive vice president of MSMA. “There is a real legal question to answer whether there’s any protections anymore.”

Holloway is concerned about the lack of protection for mothers who choose to have home births.

Dr. Ravi Johar, an OB-GYN at Mercy Clinic Women’s Health in St. Louis, said doctors have been dealing with the disasters that come in from attempted home births when unfortunate situations happen.

“There are no regulations at all on midwifery in Missouri,” Johar said. “They can do whatever they want, whenever they want with no ramifications because there is no oversight of any kind.”

Thirty states in the U.S. currently have regulations over licensure of Certified Professional Midwives, and Missouri is not one of them. Missouri is one of 10 states in which midwifery is legalized but not licensed, which means that anyone could potentially call themselves a midwife. Currently, no one in the state governmental body is proposing any regulations over CPMs.